The great thing is to last and get your work done and see and hear and learn and understand; and write when there is something that you know; and not before; and not too damned much after. Let those who want to save the world if you can get to see it clear and as a whole. Then any part you make will represent the whole if it’s made truly. The thing to do is work and learn and make it.

I bought this book because I cannot imagine any self-respecting literature enthusiast who does not own Hemingway’s major works. Admitedly, however, I did not know what to expect from the book. I had a vague notion that Hemingway discusses bullfighting – onto page one.

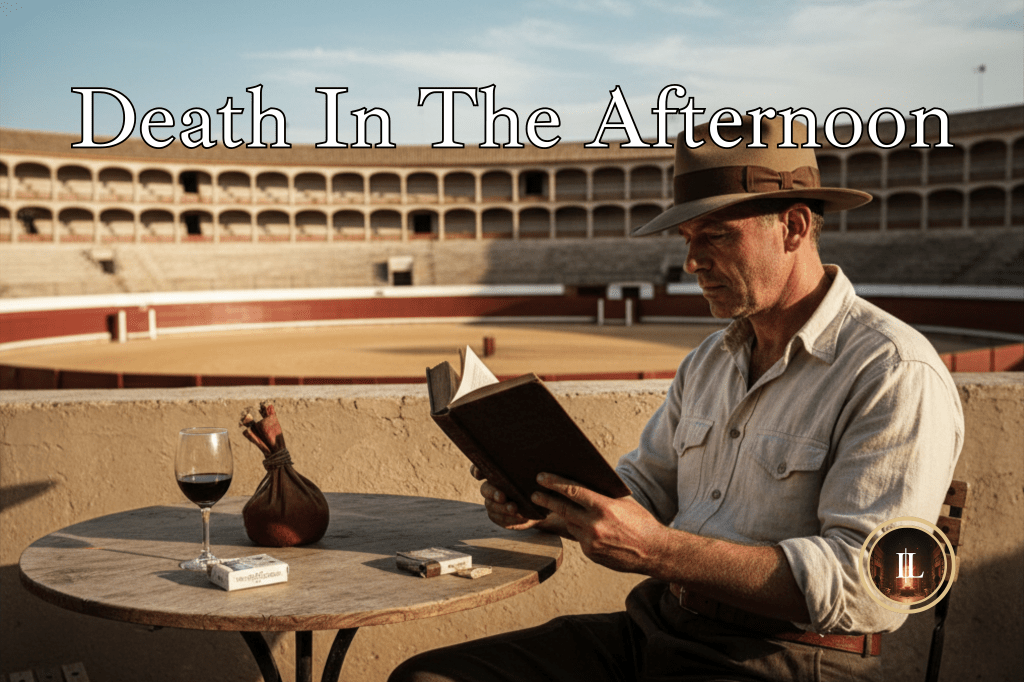

The title itself seems to suck all fear and sentiment from the notion of death. It implies a certain casual approach to the concept – or its crafty entrance onto a lively scene. Keep reading.

Immediately, Hemingway prefaces the book by dictating, in no uncertain terms, his trademark intentions as a writer – to write honestly of what exists as truth, mercilessly; the central ethos of his style. He insists that the writer must serve as a simple conduit between an event and those who read about it so the event can dictate its own inspiration to emotion, not the writer. He need not add any stimental embellishments lest the reader alternate his focus between their emotions and the writer’s emotions and displace themselves from the stirring in their own soul, or censor any aspect of an event and deny the reader the full emotive experience. Hemingway obviously possesses a deep insight into the essence of bullfighting and has coupled that insight with a sturdy writing philosophy. Preach on.

I particularly appreciated Heminway’s distinction between qualifying the moral implications of bullfighting according to feeling and as a unity of circumstances into one tragic, beautiful event. A spectator may sympathize with the horse, bull or matador which would lead to negative or positive feelings about the fight, depending on the outcome. If the matador wins and the spectator desires an example of Man triumphing over nature, he might argue for a certain moral high ground in bullfighting. Yet if a spectator sympathizes with animals, they might see only a dispicable scene of grotesque barbarity. Yet both of these spectators would miss the terrible trajedy, in all its beauty and truth, within the whole event. The bullfight, arguably, represents a dance – the unavoidable snare of Death and the proud defiance of Life – in all its terrible beauty or gallant victory.

When understanding Death as an imminent fate, one might find themselves viewing life through a rather unpleasant nihilistic lens. Such a pessimistic respect for death might ultimately render all of life’s happiness as meaningless, which would explain the moral dread felt by some who witness the bullfight. Who wants to feel that way? In the bullfight, these majestic and terrible beasts exist to die. But, nihilistically speaking, does not man exist for the same reason? Perhaps the bullfight somehow imparts Man’s dread or, perhaps, his inability to accept his own meaninglessness – born to die, a tragic existence now shared with the strongest of beasts who cannot, like Man, stave off the end.

On the other hand, Man has always imagined himself as a grandiose being capable of altering his own fate. Even today, people essentially apply all manners of sciences to disarm and shackle Death. We thrive on defiance and worship those who rise from the dead. Matadors do not rage against nature but spit in the face of charging Death. And yet, amongst all the pomp in the performance lies the art of the dance. The trajedy of the bullfight is not that the bull, or matador, dies but how he dies. Neither creature can control anything more.

One will see the brilliance and majesty of bullfighting when one sanctifies the seemingly contrary and combative executions of truth rather than abhoring the apparent neglect of cozy morals. To restrain one’s actions to align with what one can qualify as the right and true thing, though it may mean the end for something else on the stage, is to devote oneself less to the outcomes of those players and entirely to the vision of real essence. Morality cannot exist purely based on the sustainability of life because death will never cease to exist. Therefore, have confidence in doing the right thing and respect the presence of Death.

Whoa, Hemingway…careful now.

Hemingway talked at length about many of the noteworthy matadors practicing in Spain through the early twentieth century. He talked about one known as Maera. During this short biography of a John Wayne fighter brought up under one of Spain’s immortal masters, I felt a certain emotive quality but struggled to explicitly identify the reasons behind the emotion or to find any moral justification for it. At least Hemingway offered none. I simply felt the dull bliss of human connection between two unrelated people separated by all matter of space and time. Any moral implication or lesson in truth, the desire and subsequent search for them within the story, faded and left me with an indefinable contentment in knowing the true actions and essence of someone without distracting myself with the hopes of being bettered by such an acquaintance. I felt this same emotion propelling me through The Sun Also Rises but couldn’t make sense of it. After reading Death In The Afternoon, a book centering around a “sport” I care nothing about, I somehow feel that I’ve come closer to appreciating and understanding the essence of Hemingway’s ethos.

I only wish Hemingway had performed more laudibly in his craft. Look back to the epigraph at the beginning. Tell me he could not have written such a beautiful idea better.

Leave a reply to Charlotte Reads Classics Cancel reply