And what is wrong with their life? What on earth is less reprehensible than the life of the Levovs?

I grew up with a Christian mother from a small college town and a Jewish step-father from the big city. My siblings called me “the golden child” due to my success in school and for exiting my mother’s body first; for generally executing my childhood and adolescence correctly. Many conversations and episodes throughout American Pastoral resonate with me. None moreso than the Swede’s phone call with his brother at the end of Part Two, Merry’s rebellion (not her specific actions), and the Swede’s compulsion to stitch together the unstitchable.

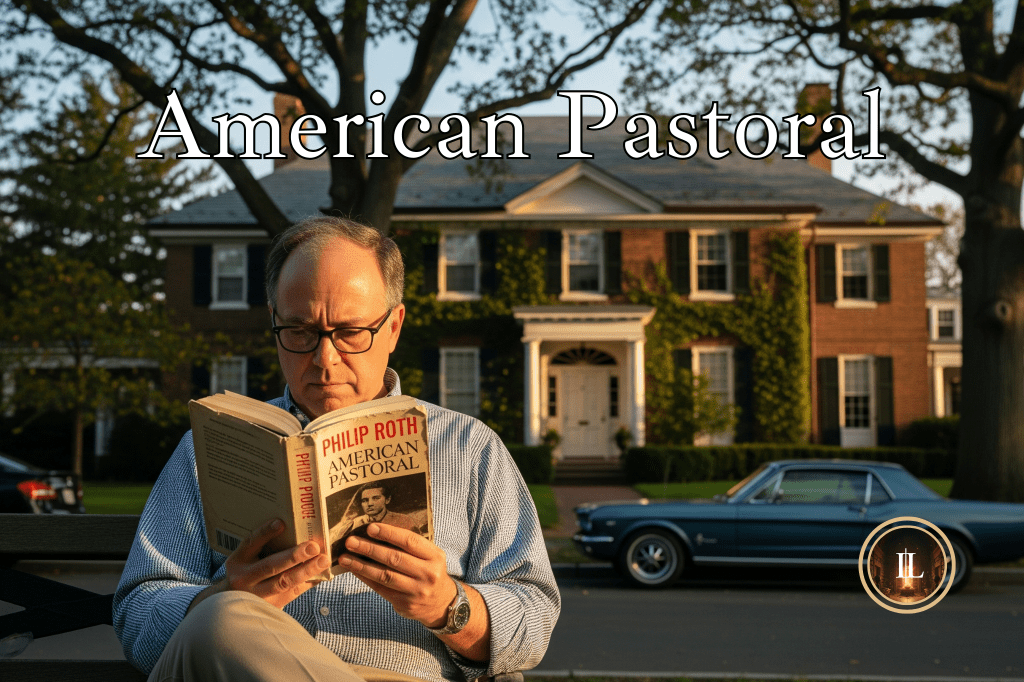

Roth spends the first part of the novel introducing the reader to the Swede, an All-American Jewish athlete blessed with a Scandanavian appearance, the strength of a mythical hero and the perfect attitude for being blamelessly worshipped. Roth begins with an autobiographical or memoir structure based on his schoolboy perspective on the Swede. Before Part Two, he writes a book about the Swede, speculating on his inner thoughts and turmoil, and sends it to his brother who tells Roth all the things that Roth got wrong. Alas, we read Roth’s book in Parts Two and Three.

This dimensionality of biography within fiction and the author’s transparency about his falibility illustrate the archetypal construct we collectively imagine of the perfect American existence; a fiction within our own biographies; a construct that destroys many of our self-efficacies as we trudge through life. Roth even tells the reader how a writer never gets a person “right” and walks a fatalistic road getting people wrong consistently and with more regularity than others. We don’t know how much of the Swede’s experience, as depicted in American Pastoral, is real, slightly embelished, or entirely imagined. Roth builds a home of truth only to set it on fire and invite us in anyway.

And in this narrative structure of the book we distinguish the overarching theme of the Swede’s story. The Swede builds the perfect American life – an All-American athlete who inherits his father’s glove manufacturing business, marries Ms. New Jersey, moves to the quintessential Americana suburb – only to find it burning down and himself unable to find a cause; inept at stitching the frayed bits of the glove back together.

Furthermore, in building this aenesthitized prescription life, no one really knows the Swede. He does not act not like himself nor does he act like himself. He spends all his energy building what he thinks will make those around him happy; taking over the family business rather than pursuing an athletic career, coaching his Irish Catholic wife through interviews with his Jewish father like a pageant coach then failing to intercede on her behalf as it happens, raising his daughter without tough love…whatever he has to do to keep the waters calm and the waves crashing on another beach. Make no stance on anything, no decisions, no boundaries. Keep the peace.

His daughter actively destroys that peace and his anguish begins – the innocent anguish of a father doing his best, of course. I think readers learn, before the Swede does, that the American Pastoral, if it exists, ironically randomizes its blessings within a culture that idolizes the self-made man, worships cause and effect, imagines control, “if you work hard enough”. And yet through grinding gears of multiple generations around the family dinner table, Roth unveils the cold, ineffectual progress americana stampeding those in its path.

There is a certain nihilism in the American Dream like in parenting. We control very little in the outcome of the next generation as they navigate a completely new world than the one to which their forebears finally adapted.

I enjoy Roth’s creativity in this portrait; his structure, his language and the embittered passion that burns through each page. We don’t know if Roth got the Swede right or wrong, but I think the reader understands the conflict between Americans and the value America projects onto her citizens by a culture we impose on ourselves. We build our lives with the promise that things will work out if we follow the American mantra only to find that America lacks the strength to hold back nature or save us from life.

Leave a comment