Outside the world, outside the past, outside myself: freedom is exile, and I am condemned to be free.

He did it again. Such rich language! Such unique style! Such poignant literary choices!

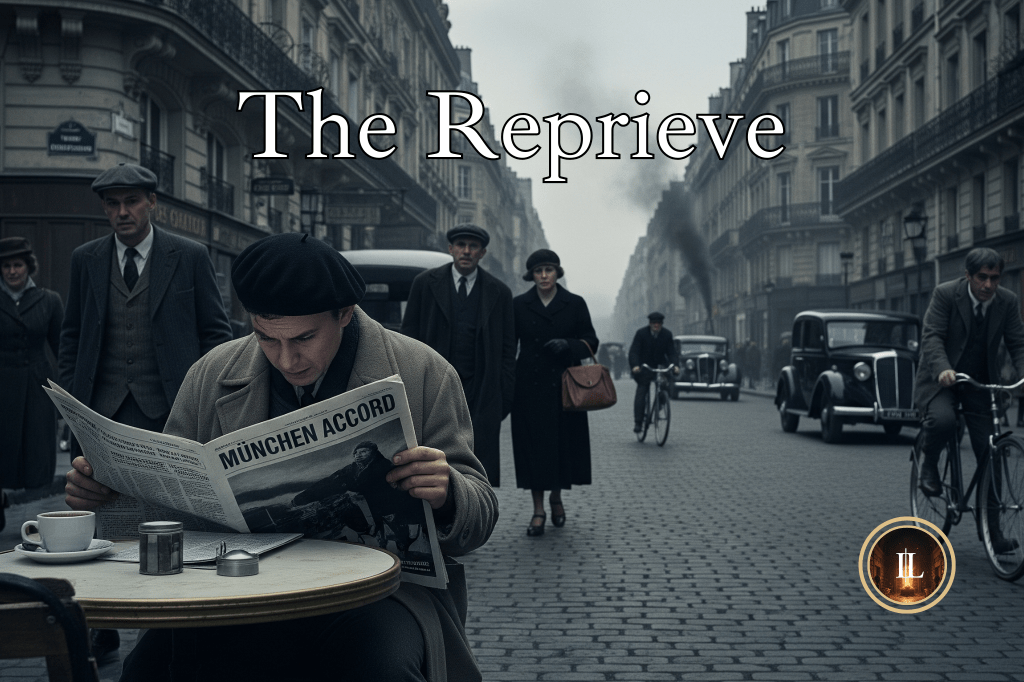

In this second installment in The Roads To Freedom, we stand at the brink of war alongside Mathieu, Daniel, Ivich, Boris, Lola and our other comrades from The Age of Reason. And we meet an abundance of new characters as well. Through the entire novel, Sartre spans the time of one week. Yet within that week we find eternity in which beginning and end and all points of self-discovery between exist eternally.

In The Reprieve, Sartre applies a different narrative structure than in The Age of Reason. He cleverly dances between multitudes of different characters and their storylines. But each pivot happens without any warning to the reader; sometimes mid-sentence. Pronouns used when reading about Mathieu and Gomez suddenly shift to Maud and Pierre and one must catch the change by the subtle shift in setting or other indicators to avoid prolonged confusion. At first, I found the narrative difficult to follow but, if nothing else, it forced me to stay alert and hang on every sentence; for which I am grateful.

Why do this? As I jorneyed deeper into the novel, I realized that this tactic illustrates ideas central to Sartre’s understanding of these times – the essence of the individual and collective as well as eternity when faced with destruction. All of Europe stands at the brink of world war and, while his stories focus on individual experiences in this shared dilemma, the narrative combines these experiences into a single stream of humanity as if humanity itself were an organism. I imagine one could graph the pivots and find further significance in Sartre’s choices of when to change, to whom to shift, and for how long.

Within these shifts, one also also notices the comparisons and contrasts between the characters. As familes escort their drafted soldiers to trains, we also witness nurses transporting the sick and infirm to trains; as if Sartre mirrors the soldier’s journey to the war with their foreshadowed journey from the war all in the same moment. We contrast the ignorant innocence of Gros Louis and the educated naivety of Philippe; who both end up beaten like soldier’s returning from battle. The innocence and its loss existing simultaneously within the whole of humanity and time.

The narrative not only embodies both humanity and the individual simultaneously, but also represents the essence of war in the way it encompasses all these unique episodes into a conglomeration of humanity. As individuals compile into humanity, violent activities compile into war.

War: everyone is free, and yet the die is cast. It is there, it is everywhere, it is the totality of all my thoughts, of all Hitler’s words, of all Gomez’s acts; but no one is there to add it up. It exists solely for God. But God does not exist. And yet the war exists.

What is war? What is humanity? Essences of totality collected in violent activities and unique individuals. When tangled confusingly in these snares, one understandably contemplates the essence of these contrasting concepts.

The war takes and embraces everything, war preserves every thought and every gesture, and no one can see it, not even Hitler. No one. He repeated: No one – and suddenly he caught a sight of it. It was a strange entity, and one indeed beyond the reach of thought.

Mathieu discusses the inability to see War while his counterpart, Daniel, discusses the need for something to see his Self in order to know himself.

‘I am seen, therefore I am.’ I need no longer bear the responsibility of my turbid and disintegrating self: he who sees me causes me to be; I am as he sees me.

In these contemplations, Daniel and Mathieu become quite opposite but the contrast illustrates how the wholistic essence of war and humanity cannot be known in the same way we can see and know individuality. But they both exist.

Whether individual or conceptual essence, all existence encapsulates into a single momentous experience in time; no longer linear but eternal. The reader does not come to this from character lectures or traditional fictional devices, but from the real-world artistic choices of an author composing words on bound papers in the reader’s hands.

Leave a comment