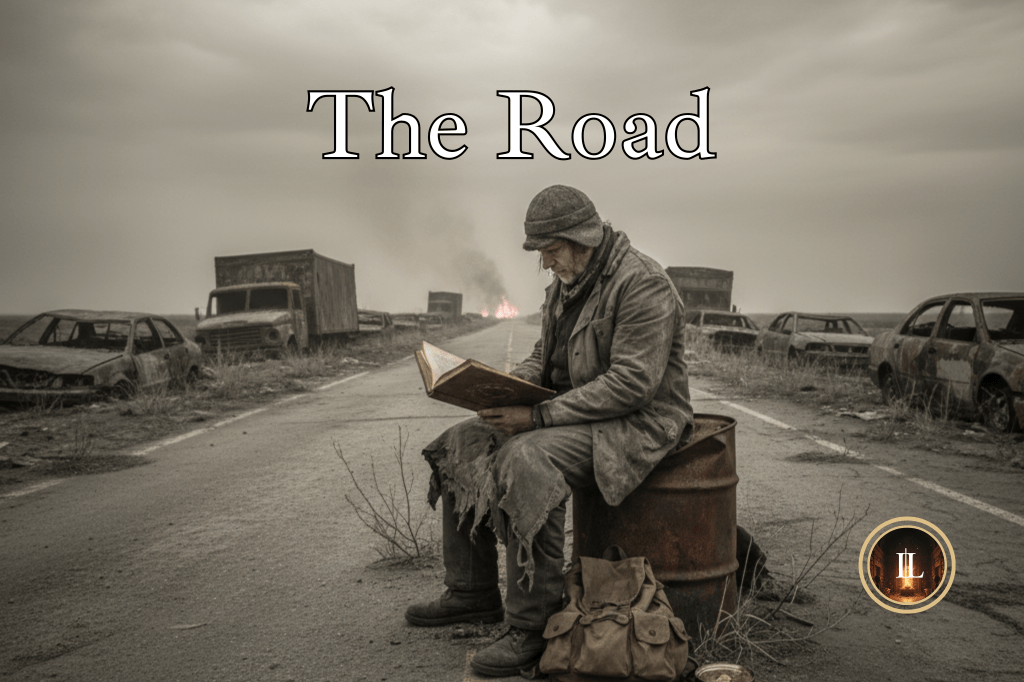

Suppose you were the last one left? Suppose you did that to yourself?

This book, in all its gloom and desperation, voices one of the most heartfelt stories of love; a bond between a father and son which hell and death itself can’t snap. McCarthy’s poetic sense of prose beautifully imagines catastrophe and the triumph of the human spirit. And to top it all off, the story poses exciting moral questions and convictions which guides that spirit.

In a world stripped of hope and comfort and left to death and desperation, morality manifests itself in basic terms of physical survival. But the juxtaposition of the man’s perspective and the boy’s perspective inspire the reader to question the fundamental qualities of life, its meaning and ultimately the value of one’s convictions.

Suppose you were the last one left? Suppose you did that to yourself?

This quote, from a conversation with an old decrepit man encountered on the road, signifies the ultimate question presented in The Road. For the sake of his son’s survival, the man adopts a moral system which dictates that he cares for no one else; offers aid to no one since it would lower the probability of he and his son’s survival. Conceptually speaking, if they don’t aid the survival of others, would this moral conviction culminate in their solitary existence on earth? By ensuring their own survival but that of no one else, are they destined to experience the ultimate loneliness, the unbearable despair that extinguishes any fathomable reason for living, crushed under the weight of despair and the yearning for death? Ultimately, does it result in the ironic end to their own survival, fearfully by their own hand?

Also, to best understand the perspective of the man, a very natural and loving perspective, no doubt, McCarthy spends some time talking about his wife. She arguably suffered from an irreconcilable conflict of interests: to end the suffering of her son and to protect him. But under these conditions, she can only end his suffering by ending his existence. Every line of thinking revolves around her son, whereas she accuses the man of needing her son simply to add purpose to his own hopeless life; a means to bolster his conviction to live.

When there is nothing else, children become our world. The son benefits from his fathers “selfish” conviction as does the man; a beautiful example of selfishness truly functioning for the betterment of people – when it benefits another, when one’s self-interest centers on the betterment of another.

The boy, who progresses from a meek innocent, suffering from normal childish fears appearing under any circumstance, to an understanding moralist, contrasts his father’s physical brand of morality with an altruistic approach to surviving. And despite this difference, the boy’s questioning and persistence sometimes overturns his father’s convictions and is ironically cultivated by his father’s own responses; as if his father’s instinctual rules for physical survival were coupled by a similar instinct to maintain an illogical hope for good. The boy knows what the man has been distracted from by intellect, rage and stress. But that distracted mentality is what keeps the boy alive, and with him his sense of the “good guys” and “carrying the fire”.

Despite these questions of morality, it is the love between father and son that nearly eliminates the possibility for these people to “do wrong”. In any case, not a single one of us would do any different than what this father and son did. It is the combination of their perspectives that define the human conviction for good; even when all of our constructive strength is squelched.

A marvelous read.

Leave a comment